Saturday, October 27, 2012

English Gothic

I like early Gothic stuff. I really like English early Gothic, especially the manuscripts,the "Matthew Paris school" stuff. This is a nice example. So what do I like about it? I like the very format of the pen drawing with the delicate tinting. I like the sharp crisp folds of the drapery. I like how the drawing violates the frame. I like the clean lines and expressive postures of the figures. I even like the lack of background.

This is a leaf from a missal for the "Parish de Pirton". The image is dated to 1220-1230. The verso of this leaf contains a 14th century charter for the rector of the church of St. John Baptist, Pirton (Worcestershire). Leaf is in the British Library (Harley Charter 83 A 37).

Friday, February 3, 2012

I made a video!!

I decided to play around with Window Lives Movie Maker, and grabbed a couple of manuscript images as material. I kept playing for a couple of days and ended up with this, a survey of illuminated manuscripts from papyrus scrolls to the Renaissance.

The choice of images is somewhat idiosyncratic, although most of the really famous manuscripts are included, there are some that are less than famous, and my own preferences may have resulted in some imbalance towards earlier manuscripts.

The music is from the Broadside Band and is decidedly anachronistic, being late 16th century. I was looking for something that sounded "medievalish" and I think it works.

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Papyrus Style

Before the invention of the codex, that is, a book made of leaves bound on one side, books were mostly on scrolls, and the predominate material for scrolls was papyrus. Papyrus was a paper like material made from a plant that grew in the Nile Delta. Greeks and Romans used papyrus as well as Egyptians, but because papyrus did not survive well in moist environments, the vast majority of papyrus survive has been found in Egypt. Because a scroll was continually rolled and unrolled, thick pigments would quickly flake off, so papyrus scrolls were not decorated or illustrated in the manner of later manuscripts, with lavish colored decorations. Scientific and mathematical texts required illustration, while illustration was optional for literary texts. Both types of texts did have illustrations though, and in a similar style, called by Kurt Weitzman called the "papyrus style". In the papyrus style, small, quickly drawn, ink illustrations would be inserted into gaps in the text block. The were seldom colored and usually had little if any background or framing.

Few examples of illustrated papyri remain, and thoe only in fragments. One example is the so-called Heracles Papyrus. It consists of two columns of text which have three quick sketches of Heracles fighting the The Nemean lion.

The iconography of the sketches is fairly conventional, compare the second sketch with this roughly contemporary mosaic from Spain.

Not all works on Papyrus were quick, rough sketches. The Charioteer Papyrus (pictured at top) is a fragment containing a finely drawn colored illustration of six chariot charioteers. There is no text on the fragment, so it is not known what work it illustrated. Indeed it cannot be said with certainty is came from a scroll or an codex.

The Papyrus style was carried over into early codices, although it was eventually abandoned because of the new opportunities provided by the new format

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Chuldov Psalter

The Chludov Psalter is one of the few surviving 9th century Byzantine manuscripts. The early part of the 9th century was a period of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire. The Iconoclasm was a reaction against the use of religious images. During this period many works of art were destroyed. The Chludov Psalter was made either in secret during the Iconoclasm or after the restoration of icon, as a polemic against the Iconoclasm. In this illustration, the act of painting over an icon is paired with the Crucifixion, comparing those who destroyed icons to those who crucified Christ. To the right of the text a soldier offers Jesus a sponge filled with vinegar, while below the iconoclast Patriarch of Constantinople, John the Grammarian is seen painting over an icon of Christ using similar sponge attached to a pole. Even the pot for the the patriarch's paint is similar to the pot holding the vinegar used by the soldier.

Thursday, December 9, 2010

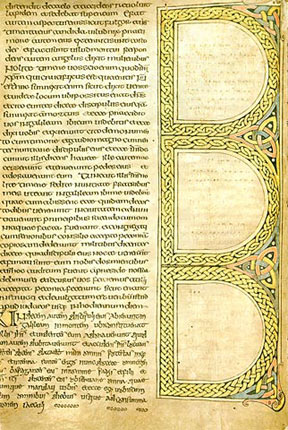

Carpet Page, Lindisfarne Gospels

Others may rave about the Chi Rho monogram from the Book of Kells, but for my money, this is the single most impressive piece of illumination from the Middle Ages. This is one of the carpet pages from the Lindisfarne Gospels. It's said that each of the carpet pages in the Lindisfarne Gospels have an intentional error in the knotwork. Good luck finding it.

Monday, July 26, 2010

Orion from Leiden Aratea

Orion the Hunter from the Leiden Aratea. This is one of the great works of the Carolingian Renaissance, which how shows how thoroughly classical art was revived. This is such a close copy of its late antique model that is it was at one time thought to be of late antique provenence itself. Note the use of shading to model Orion's musculature. This had not been done in a realistic way for centuries when this manuscript was made. The text in this manuscript is know as the Aratea is by Germanicus and is based on the Phainomena of Aratus and is an introduction to the constellations. Germanicus is best remembered as the popular adoptive grandson of Augustus and grandfather of Nero. In Graves I, Claudius he was poisoned by Livia and Caligula. The Leiden university library has posted a digital facsimile of the manuscript here.

Leiden Aratea Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Voss. lat. Q 79, f. 58v.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Chi Rho monograms.

Last night I talked a bit about the Chi Rho monogram in the Stockholm Codex Aureus. It got me thinking about how often these monograms show up in insular gospel books. So I decided to see how may I could find and spent a couple of hours poking around looking for images of them. This is by no means a comprehensive list, but here are the ones I found, in roughly chronological order.

First up is the Book of Durrow, dating to the middle of the 7th century. The Chi is enlarged, the Rho slightly smaller, the whole line is enlarged and set off and colored yellow. It is n0t really known where the manuscript was made, although it was probably made somewhere in Ireland.

First up is the Book of Durrow, dating to the middle of the 7th century. The Chi is enlarged, the Rho slightly smaller, the whole line is enlarged and set off and colored yellow. It is n0t really known where the manuscript was made, although it was probably made somewhere in Ireland. Durrow is followed by the Lindisfarne Gospels of about 7o0. This is a quantum leap with the Chi Rho dominating the page. The Chi and the Rho are extensively decorated. All of the text on the page is turned into one large decorative pattern. One of my favorite things about the Lindisfarne Gospels is how the artist would "draw" with the decorative red dots found in so many insular manuscripts. Here he has "written" with them to form the letters of the line following the Chi Rho monogram completely out of the red dots. The Lindisfarne Gospels are known to have been produced on the Island of Lindisfarne off the east coast of Northumberland.

Durrow is followed by the Lindisfarne Gospels of about 7o0. This is a quantum leap with the Chi Rho dominating the page. The Chi and the Rho are extensively decorated. All of the text on the page is turned into one large decorative pattern. One of my favorite things about the Lindisfarne Gospels is how the artist would "draw" with the decorative red dots found in so many insular manuscripts. Here he has "written" with them to form the letters of the line following the Chi Rho monogram completely out of the red dots. The Lindisfarne Gospels are known to have been produced on the Island of Lindisfarne off the east coast of Northumberland. Next up is an unnamed manuscript in the British Library (Royal MS 1 B VII). This is a smaller scale effort, as this is not as sumptuous of a manuscript. The zoomorphic Chi Rho Initial is as about as large as the initials which begins each of the gospels. The scribe started a new column at the Chi Rho initial, as if he were starting a new work, leaving the bottom of the left column blank. (The text in the obviously different script at the bottom of the left hand column is a later addition, a manumission of a slave in Old English.) This manuscript was produced in the first half of the 8th century in Northumbria.

Next up is an unnamed manuscript in the British Library (Royal MS 1 B VII). This is a smaller scale effort, as this is not as sumptuous of a manuscript. The zoomorphic Chi Rho Initial is as about as large as the initials which begins each of the gospels. The scribe started a new column at the Chi Rho initial, as if he were starting a new work, leaving the bottom of the left column blank. (The text in the obviously different script at the bottom of the left hand column is a later addition, a manumission of a slave in Old English.) This manuscript was produced in the first half of the 8th century in Northumbria. Next is the St. Gall Gospels, now housed in the monastery at St. Gall in Switzerland. This manuscript was produced by monks in Ireland about 750 and brought with them when St. Gall was founded. By this point, Chi is taken over the page, leaving room for only a few words of additional text, which is so stylized and decorated as to be unreadable. (This and Lindisfarne are my two favorites.)

Next is the St. Gall Gospels, now housed in the monastery at St. Gall in Switzerland. This manuscript was produced by monks in Ireland about 750 and brought with them when St. Gall was founded. By this point, Chi is taken over the page, leaving room for only a few words of additional text, which is so stylized and decorated as to be unreadable. (This and Lindisfarne are my two favorites.) Next up is our friend from last night, the Stockholm Codex Aureus. This is somewhat more restrained, although the text is seen as a decorated pattern with legibility allowed to be lost to aesthetics. This manuscript was produced somewhere in Southumbria, probably Canterbury. The influence of the Roman Church mission at Canterbury probably exerted a restraining influence on the wilder "Celtic" traditions seen in more northern insular manuscripts. This manuscript dates to about 750.

Next up is our friend from last night, the Stockholm Codex Aureus. This is somewhat more restrained, although the text is seen as a decorated pattern with legibility allowed to be lost to aesthetics. This manuscript was produced somewhere in Southumbria, probably Canterbury. The influence of the Roman Church mission at Canterbury probably exerted a restraining influence on the wilder "Celtic" traditions seen in more northern insular manuscripts. This manuscript dates to about 750. This one needs no introduction. It is, of course, the Chi Rho page from the Book of Kells and easily one of the most famous manuscript images of the middle ages. Exuberance abounds and there is no restraint. (Despite its fame, I still like Lindisfarne better. Does that make me a heretic?)

This one needs no introduction. It is, of course, the Chi Rho page from the Book of Kells and easily one of the most famous manuscript images of the middle ages. Exuberance abounds and there is no restraint. (Despite its fame, I still like Lindisfarne better. Does that make me a heretic?)

This is from another unnamed manuscript in the British Library, (Royal MS 1 B VII). In a sense Kells was at once the culmination and last gasp of the Insular tradition. After Kells the Carolingian Renaissance got underway, and the insular style fell out of favor. The truly deluxe manuscripts of the era looked to classical models. Still some manuscripts were made in the Insular style. This manuscript is from about a century after Kells. Although the Chi Rho monogram is present it is more closely related to the zoomorphic initial of the other unnamed British Library manuscript than to the Durrow, Lindisfarne, St. Gall, and Kells.

This is from the the Bodmin Gospels which was made in the 9th or 10th century. This is not a deluxe manuscript, so, although the Chi is emphasized it is not a major piece of illumination.

This is from the Book of Deer, which was made in Scotland in the 10th century. One day I will have to talk more about this manuscript in detail. It is a relatively small scale, somewhat odd manuscript, but is clearly still following the Insular tradition.

This is from the Book of Deer, which was made in Scotland in the 10th century. One day I will have to talk more about this manuscript in detail. It is a relatively small scale, somewhat odd manuscript, but is clearly still following the Insular tradition. This is the Corpus Irish Gospels, now owned by Corpus Christi College, Oxford. It was produced in the twelfth century, almost 500 years after the Book of Durrow. It, along with the next manuscript show the extreme tenacity with which this style had in Ireland. This monogram with its interlace decoration on spiral motifs would be at home in manuscripts centuries older.

This is the Corpus Irish Gospels, now owned by Corpus Christi College, Oxford. It was produced in the twelfth century, almost 500 years after the Book of Durrow. It, along with the next manuscript show the extreme tenacity with which this style had in Ireland. This monogram with its interlace decoration on spiral motifs would be at home in manuscripts centuries older.

My final manuscript is the Gospels of Mael Brigte, which are firmly dated by a colophon to 1138. Although simpler in decoration than the the Corpus Gospels, this manuscript is also done in the insular style, centuries after the style's high point and shows the enduring popularity of the style in Ireland.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Stockholm Codex Aureus

This is the Stockholm Codex Aureus (Stockholm, Royal Library, MS A. 135), also known as the Codex Aureus of Canterbury. "Codex Aureus" can be translated as "Golden Book" and refers to the liberal use gold leaf used in the decoration of this manuscript. There are several other manuscripts known as the Codex Aureus as well, so you have to specify which one you are dealing with. Stockholm refers to its current location, while Canterbury refers to where it was probably made.

This is the Stockholm Codex Aureus (Stockholm, Royal Library, MS A. 135), also known as the Codex Aureus of Canterbury. "Codex Aureus" can be translated as "Golden Book" and refers to the liberal use gold leaf used in the decoration of this manuscript. There are several other manuscripts known as the Codex Aureus as well, so you have to specify which one you are dealing with. Stockholm refers to its current location, while Canterbury refers to where it was probably made.This is a Gospel Book and contains the Latin text of the four gospels. (I'm not sure what version, but I would bet that it is the mix of Vulgate and Vetus Latina found in other insular gospels). I also don't know what texts, other than the Gospels it contains, although I do know that it has Canon Tables. I would assume that some of the prefatory matter found in other Insular Gospels is present. There are 193 extant folios. Alternating folios have been dyed purple. The text is written in an uncial script in black, white, red, gold and silver inks. There are two surviving evangelist portraits, six decorated canon tables and seven decorated initials.

The portrait of Matthew shown here, is quite different from the highly stylized and abstracted portraits in other Insular manuscripts. Matthew is seated on throne within an arcade with pillars. Curtains hanging from above are wrapped around the pillars. In the tympanum above is his symbol, the winged man. There is little in the way decoration and the composition lacks the elaborate decorated borders found in some of the other insular manuscripts. Although the elements, including Matthew himself, are stylized and flattened the entire composition has a serene monumental quality. In many ways, this can be seen as a precursor to later Anglo-Saxon and Carolingian styles.

The facing text page, however, would be comfortably at home in any of the great Insular manuscripts like Kells or Durrow. The text block and each line of text is contained within a frame. The text lines alternate between a gilded background and golden letters, creating a dazzling effect. The opening initial is an elaborate monogram decorated with interlaced patterns and laid on a background of spiral motifs. As can be seen by the detail below, the draftsmanship is quite high.

That the evangelist portrait faces this page is quite interesting. The initial monogram is of the Greek letters Chi and Rho (XP). This monogram was often used as in place of the word for "Christ". The interesting thing is that, although evangelist portraits were usually placed at the beginning of a gospel, this is not the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew. This is the text which begins at Matthew 1:18. The preceding 17 verses contain a genealogy of Christ, and the actual narrative of Christ's life starts here. In insular manuscripts, the genealogy was often treated almost as a separate work and this "second beginning" was often given its own frontispiece, although this is the only manuscript that I am aware of that moves the evangelist portrait here. The enlarged, decorated Chi Rho monogram at this point in the text is a motif that is limited to insular gospel books.

This manuscript was at Christ Church, Oxford in the 9th century. It was looted by the Vikings, ransomed by Earl Alfred (later King Alfred). At some time in the middle ages it was lost again. It was found by a Swede in 1690 in Spain and purchased for the Swedish Royal Library

Monday, April 20, 2009

Manuscripts on the web: The British Library

So, I like to go looking around the web for pretty pictures. One type of pretty picture I look for is illuminated manuscript images. One thing that I've found is that several institutions have done a great job digitizing images and making them available. Here are some of the places I've found.

Let's start with the big one. The British Library. The British Library, of course, has one of the best collections in the world. The Bibliotheque Nationale and the Vatican Library are the only close contenders I can think of.

The British Library is fairly generous, there are three ways they make manuscripts available. The big one is their Catalogue of Illuminated manuscripts. Thousands of manuscripts are cataloged here. (Over 1500 from the Harley collection alone.) Each manuscript has a upwards to twenty or so images available. The down side is that they are going methodically through the collections, and they haven't included the Cotton or Additional Manuscript collections yet, and that is where a lot of the really good stuff is.

Equally impressive is their Online Gallery of illuminated manuscripts. This used to be part of their Collect Britain site, and focused on manuscripts made in Britain. Each page is treated as separate work, but you can search by shelfmark. There are plenty of images of little known manuscripts. There are also illuminated manuscript images scattered through some of the other galleries. The Online Galleries also has a Virtual Books section with in depth looks at several important books including a late 17th cent Ethiopian Bible, the "Golf Book, the Luttrell Psalter, the Golden Haggadah, a 15th Century Hebrew Bible from Lisbon, the Sforza Hours, the Sherborne Missal, and the Lindisfarne Gospels. I can't make this feature work due to limitations of my computer and my lack of Geek skills.

A final place to look for images is the Images Online. This is primarily intended as a site to sell high quality images, but their previews are good enough quality for casual browsing. You can find images from many manuscripts not found at the other Brirish Library sites.

Finally for the British Library if you are looking for information on manuscripts, but not images, there is the Manuscript Catalogue. The entries in the catalog range from fairly complete articles, with bibliography to a few words in Latin.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Codex Manesse

The Codex Manesse (Heidelberg, University Library, Cod. Pal. germ. 848) is a German manuscript, which was produced in Zürich between 1304 and 1340. It is an important literary manuscript, as it is the single most comprehensive source of Middle High German love songs, the songs of the minnesängers. There are 140 poets represented, who range in social status from the Emperor Henry VI to commoners. As important as the manuscript is for literary history, it is best known for its illuminations. There are 137 portraits of poets, many of them shown in full armor with heraldic devices. These illuminations have been widely reproduced, so much so that are almost the stereotype of High Medieval art. The last I was at Barnes and Noble I noticed at three books with cover art drawn from the Codex Manesse. The illustrations have also been widely used as decorative motifs. I have some wooden plaques with reproductions of some of these pages on my walls right now. Here are some of the images.

And, since this is a manuscript of songs, here is recreation of one of the songs.

Wednesday, July 2, 2008

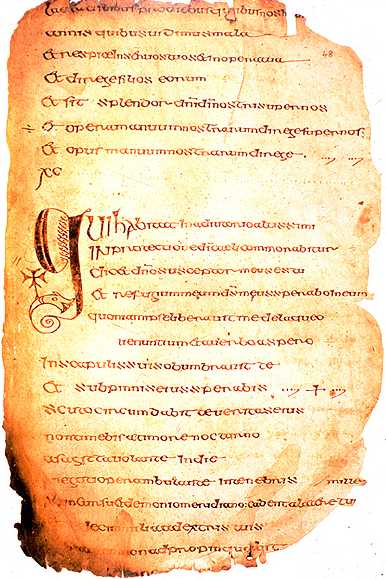

Durham Cathedral Library, MS A II 10

First a little bit about the "name" of this manuscript. If you are already familiar with how shelfmarks work, you can skip to the next paragraph. Many manuscripts are famous and have names that are well known outside of the realm of medievalists, the Book of Kells for example. Others are more obscure, but are well known to medievalists, the Quedlinburg Itala or the Vatican Virgil, for example. Others may have names that uniquely identify them, but are not well known to anyone other than a specialist. Most manuscripts don't have names, though, and are identified only by shelfmarks. Shelfmarks are the cataloging labels given to each manuscript by the institution that holds it. Each institution makes its own rules as to how to assign shelfmarks. Some just number them; MS 1, MS 2, etc. Others will sort by their manuscripts into collections, and number each collection. The collections may be sorted by language, or manuscript type, or by donor. Some large institutions might have several different types of collections. In any case, the full shelfmark will identify a manuscript precisely. (Some institutions that only hold a few manuscripts, or perhaps only one, don't use shelfmarks at all.) These shelfmarks are a kind of secret passwords for medievalists. You stand a much better chance of getting an institution to let you look at a manuscript if you know its shelfmark. Some institutions, rather than simply numbering the manuscript, use a more complicated scheme, that gives you the precise location of the manuscript. To do this you must identify the bookcase a manuscript is in, the shelf of the bookcase, and the position of the manuscript on the shelf. This is what Durham Cathedral does. This manuscript is A II 10. This translates to the first bookcase (A), the second shelf (II), and the tenth manuscript (10).

First a little bit about the "name" of this manuscript. If you are already familiar with how shelfmarks work, you can skip to the next paragraph. Many manuscripts are famous and have names that are well known outside of the realm of medievalists, the Book of Kells for example. Others are more obscure, but are well known to medievalists, the Quedlinburg Itala or the Vatican Virgil, for example. Others may have names that uniquely identify them, but are not well known to anyone other than a specialist. Most manuscripts don't have names, though, and are identified only by shelfmarks. Shelfmarks are the cataloging labels given to each manuscript by the institution that holds it. Each institution makes its own rules as to how to assign shelfmarks. Some just number them; MS 1, MS 2, etc. Others will sort by their manuscripts into collections, and number each collection. The collections may be sorted by language, or manuscript type, or by donor. Some large institutions might have several different types of collections. In any case, the full shelfmark will identify a manuscript precisely. (Some institutions that only hold a few manuscripts, or perhaps only one, don't use shelfmarks at all.) These shelfmarks are a kind of secret passwords for medievalists. You stand a much better chance of getting an institution to let you look at a manuscript if you know its shelfmark. Some institutions, rather than simply numbering the manuscript, use a more complicated scheme, that gives you the precise location of the manuscript. To do this you must identify the bookcase a manuscript is in, the shelf of the bookcase, and the position of the manuscript on the shelf. This is what Durham Cathedral does. This manuscript is A II 10. This translates to the first bookcase (A), the second shelf (II), and the tenth manuscript (10).This manuscript is a fragment of an early Insular gospel book. It is usually known only by the its shelfmark because there are at least two other fragmentary Insular gospel books at Durham Cathedral (MSS A II 16, and A II 17). MS A II 17 is sometimes called the "Durham Gospels". Kirsten Ataoguz at Early Medieval Art calls this the "Earlier Durham Gospels" and A II 17 the later Durham Gospels.

This manuscript is earliest in a sequence of magnificently decorated gospel books that stretches to the Book of Kells and beyond. This manuscript dates to the early 7th century and is not much younger than the Cathach of St. Columba. The surviving fragments contain two important pieces of decoration, on facing pages. Folio 3v* (see illustration above) contains the end of the the Gospel of Matthew. The text is in the left hand column, the other column contains a frame shaped like three capital letter "Ds" stacked one on top of the other. Each frame is decorated with a knot work pattern, and each frame has a different pattern. (Dr. Ataoguz suggests having students describe these patterns as an exercise in observation and description. Other than noting that the lower 'D' is decorated with a traditional three strand braid, I would find this very difficult.) The triangular spaces between, above and below the "D" frames are filled with larger, looser triangular knots. Inside the frames are written the explicit** to Matthew, the incipit** to the Gospel of Mark, and the Pater Noster, or Lord's Prayer, in Greek, but written in Latin letters. Facing this page is the opening page to the Gospel of Mark. (see illustration at right.) It starts with a large decorated initial. This initial takes the first three letters of the the opening word "Initium" and fuses them into a large monogram. The monogram is shorter on the right side than it is on the left. Each subsequent letter in the opening word is smaller than the preceding letter. This diminuation of letters was first seen in the Cathach. A manuscript of Jerome at Bobbio from the early 7th century also contains an "INI" monogram that is very similar in form to this monogram (see illustration below). This would suggest a fairly wide spread artistic convention.

This manuscript is earliest in a sequence of magnificently decorated gospel books that stretches to the Book of Kells and beyond. This manuscript dates to the early 7th century and is not much younger than the Cathach of St. Columba. The surviving fragments contain two important pieces of decoration, on facing pages. Folio 3v* (see illustration above) contains the end of the the Gospel of Matthew. The text is in the left hand column, the other column contains a frame shaped like three capital letter "Ds" stacked one on top of the other. Each frame is decorated with a knot work pattern, and each frame has a different pattern. (Dr. Ataoguz suggests having students describe these patterns as an exercise in observation and description. Other than noting that the lower 'D' is decorated with a traditional three strand braid, I would find this very difficult.) The triangular spaces between, above and below the "D" frames are filled with larger, looser triangular knots. Inside the frames are written the explicit** to Matthew, the incipit** to the Gospel of Mark, and the Pater Noster, or Lord's Prayer, in Greek, but written in Latin letters. Facing this page is the opening page to the Gospel of Mark. (see illustration at right.) It starts with a large decorated initial. This initial takes the first three letters of the the opening word "Initium" and fuses them into a large monogram. The monogram is shorter on the right side than it is on the left. Each subsequent letter in the opening word is smaller than the preceding letter. This diminuation of letters was first seen in the Cathach. A manuscript of Jerome at Bobbio from the early 7th century also contains an "INI" monogram that is very similar in form to this monogram (see illustration below). This would suggest a fairly wide spread artistic convention.This manuscript, fragmentary as it is, is still quite important. It is has the first surviving appearance of the knotwork that would a major motif in later Insular manuscripts. The later Insular gospel books would all use monograms similar to the "INI" monogram used here. It shows the continuation of the strong tradition of the diminuation of letters after an enlarged intitial.

The Bobbio Jerome initial. My apologies for the low quality of the image.

* Most manuscripts were not paginated as modern books are. In modern books, each side of a single leaf is given a new page number. Manuscripts are usually foliated, where each leaf is give a number. The two sides are then termed the "recto" and the "verso". The recto is the "front" side, that is the side that is on the right side of the book when it is opened. The other side, the verso is on the left side of the open book. Individual sides of folios are indicated by giving the folio number and an "r" or "v" for recto or verso.

**The incipit and explicit are the terms for text introducing announcing the beginning (incipit) and end (explicit) of a text. An incipit may read something like, "Here begins the Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Saint Matthew". For the most part, except for an occasional "The End" at the end of some novels, this practice has died out in modern books.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Bobbio Orosius

The Bobbio Orosius, from the 7th century, introduces an important motif to insular art, the Carpet Page. This is the oldest surviving carpet page. The design is not similar to the Carpet Pages in the later more famous gospel books (Durrow, Lindisfarne, Kells), but its purpose seem to have been similar; To serve as a sort of internal cover. As Dr. J. Kirsten Ataoguz points out over at Early Medieval Art, the Bobbio Orosius carpet page can be compared, at least in layout to the cover of the Stoneyhurst Gospels. (see below for image.) Like the later gospel books this carpet page faces a decorated initial. (I regret not having an image of the initial, and the poor image of the carpet page here, but it is all that is available on the net.)

The Bobbio Orosius, from the 7th century, introduces an important motif to insular art, the Carpet Page. This is the oldest surviving carpet page. The design is not similar to the Carpet Pages in the later more famous gospel books (Durrow, Lindisfarne, Kells), but its purpose seem to have been similar; To serve as a sort of internal cover. As Dr. J. Kirsten Ataoguz points out over at Early Medieval Art, the Bobbio Orosius carpet page can be compared, at least in layout to the cover of the Stoneyhurst Gospels. (see below for image.) Like the later gospel books this carpet page faces a decorated initial. (I regret not having an image of the initial, and the poor image of the carpet page here, but it is all that is available on the net.)The Bobbio Orosius also represents an important movement in the religious and artistic history of Europe. Although the manuscript was produced at a monastery in Italy, it was produced by Irish monks. The monastery in question, Bobbio was founded by St. Columbanus, who was from Ireland. Many important communities on the continent were founded by Irish monks. Many of the important "insular" manuscripts were in fact produced in the scriptoria of these communities. These monasteries were to play a vital role in the religious and artistic life of the next several centuries.

The manuscript itself (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana MS D. 23. Sup.) is a copy of the Chronicon of Orosius. In the seventtenth century it was given to the newly established Ambrosian Library in Milan, where it remains today. Dr. Ataoguz also has a discussion of this manuscript at Early Medieval Art.

The Stonyhurst Gospel Covers

Saturday, June 7, 2008

Cathach of St. Columba

The Cathach of St. Columba is the starting point for Celtic manuscripts. The traditional story is that Columba was lent a psalter by St. Finnian on the condition that he not copy it. Columba nevertheless copied in a single miraculous all-night session. When Finnian discovered the manuscript, he appealed to the local king, who awarded the copy to Finnian. Columba raised his kinsmen which resulted in the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne. Columba went into exile, where he founded Iona, as penance for the men killed in the battle. The Cathach is traditionally identified with Columba's copy. The Cathach, however, has been dated to the 7th century on paleological grounds. Throughout the Middle Ages it was carried into battle as a talisman, a practice from which it gets it name. "Cathach" means "battler" in Irish.

The Cathach of St. Columba is the starting point for Celtic manuscripts. The traditional story is that Columba was lent a psalter by St. Finnian on the condition that he not copy it. Columba nevertheless copied in a single miraculous all-night session. When Finnian discovered the manuscript, he appealed to the local king, who awarded the copy to Finnian. Columba raised his kinsmen which resulted in the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne. Columba went into exile, where he founded Iona, as penance for the men killed in the battle. The Cathach is traditionally identified with Columba's copy. The Cathach, however, has been dated to the 7th century on paleological grounds. Throughout the Middle Ages it was carried into battle as a talisman, a practice from which it gets it name. "Cathach" means "battler" in Irish.The decoration in the Cathach is limited to the first few letters of each Psalm. This decoration establishes several themes that are explored in great depth in later manuscripts. The first letter of each Psalm is enlarged. In earlier manuscripts initial letters had been enlarged and decorated. Bit the decorations in those manuscripts were used to fill space or were appended to the latter. In the Cathach, the decoration distorts the shape of the letter, so that the letter becomes the decoration. Subsequent letters were drawn into the decoration through the gradual shrinking of the letters. In earlier manuscripts the letters after the first letter were the same size as the he rest of the text. In the Cathach, each subsequent letter is a bit smaller than the preceding letter until the letters reach the size of the bulk of the text. The letters are often decorated with small red dots. These three ideas the distortion of letters for decoration, the dimidation of letters, and the use red dots for decoration are ideas worked out in great detail later.

Monday, June 2, 2008

5th century Coptic manuscript.

This manuscript represents a bit of a frustration for me. I had read Weitzmann, and some other sources so I thought I had a pretty good idea what were the important manuscripts. Then I checked out Lorenzo Crinelli's, Treasures from Italy's Great Libraries

All of that aside, so that you won't have go read the Wikipedia article, here are the basics. This is a fragment of 5th century manuscript of the Old Testament written in the Coptic language. The manuscript has only 8 surviving folios and includes the text from the Book of Job and from Proverbs. One folio has a large pen drawing illustrating Job and his daughters with Job pictured as a bearded man wearing a crown and short tunic. His daughters wear tunics with jewels and diadems. The iconography of Job is very different in this manuscript from that in later centuries. Here he is seen as royal figure while in later portrayals he is seen as humbled and sitting on a dung heap.

Thursday, February 14, 2008

Illuminated manuscripts, the beginning

Manuscript illumination, in the broadest sense, covers the decoration or illustration of any written text. The practice started with the Egyptians, who would illustrate portions of The Book of the Dead that would be buried with mummies. One can assume that they illustrated other texts, but so few of those survive it is hard to tell. They certainly would have had to have illustrations in geometry texts. The oldest surviving illustrated text is in fact not from The Book of the Dead, but of a play written to celebrate the accession of Pharaoh Senusret I. It dates to about 1980 BC. Surely other illustrated texts existed.

The Greeks seemed to have learned the practice from the Egyptians. It is significant that there is no evidence of the Greeks illustrating texts before the conquests of Alexander. The Greeks used what Kurt Weitzmann called the "papyrus style", which the Egyptians also used. Since the texts were written on scrolls, heavy paint could not be applied, like it can be to flat pages, as the repeated rolling would cause it to flake off. Instead quick pen and ink drawings were inserted into the columns of text. Pictured here is a papyrus fragment known as the Heracles Papyrus (Oxford, Sackler Library, Oxyrhynchus Pap. 2331) . It tells a portion of the tale of the Twelve Labors of Heracles (or Hercules, if you're feeling Roman), specifically that of the Nemean Lion. Three simple drawings of are inserted into the text columns illustrating the story. Perhaps the drawings were inserted to help a reader quickly find his place in the text, or perhaps because people like pictures. This fragment dates to 3rd century AD, and is one of the few fragments from the classical period illustrating a literary text. Because so few fragments survive, it is impossible to tell if scrolls existed with a higher quality of illustration.

Monday, February 4, 2008

Caligula Troper

This is a page from the Caligula Troper (British Library, MS Caligula A XIV). A troper is a collection of tropes, which were new music inserted into the chants of the mass for special feast days. This book was intended to be used by a soloist, and was of a small scale. The opulence of the decoration indicate that it was made for an important patron. The tropes included in the manuscript indicate that it may have been made in Winchester or Worcester. It was made in about 1050. This page has an image of the Wise Virgins (Matthew 25:1-13) as an illustration for the mass for Virgin Saints. The Virgins hold the lamps and torches from the parable, along with branches, which may represent the the palms of martyrdom. The Hand of God blesses them from above. The Virgins' robes are abstracted into a geometric pattern and the are placed against a gold background which gives an unworldly, spiritual feel to the illustration.

This is a page from the Caligula Troper (British Library, MS Caligula A XIV). A troper is a collection of tropes, which were new music inserted into the chants of the mass for special feast days. This book was intended to be used by a soloist, and was of a small scale. The opulence of the decoration indicate that it was made for an important patron. The tropes included in the manuscript indicate that it may have been made in Winchester or Worcester. It was made in about 1050. This page has an image of the Wise Virgins (Matthew 25:1-13) as an illustration for the mass for Virgin Saints. The Virgins hold the lamps and torches from the parable, along with branches, which may represent the the palms of martyrdom. The Hand of God blesses them from above. The Virgins' robes are abstracted into a geometric pattern and the are placed against a gold background which gives an unworldly, spiritual feel to the illustration.The manuscript names comes form its position in the Cotton Library. Robert Cotton was a 17th century bibliophile. He kept his manuscripts in case above which were busts of Roman emperors and Ladies. These busts were used to Catalog the manuscripts. This manuscripts shelfmark, Caligula A XIV meant that the manuscript was in the case under the bust Caligula, on the first shelf, and 14th book from the left. When the Cotton Library became one of the foundational collections of the British Library, its shelfmarks were retained.

Friday, February 1, 2008

Vatican Virgil

This is a page from the Vatican Virgil (Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica, Cod. Vat. lat. 3225). This is one of the oldest surviving illuminated manuscripts, dating to about 400. It is one of only three surviving illustrated manuscripts of classical literature from the classical period. In a one sense, this is where manuscript illumination started. The style is similiar to the frescoes found at Pompeii and in the Roman catacombs. They are typical of late Roman painting, showing an illusionistic treatment of space and modeling of the human form. There are 77 surviving leaves with 50 illustrations. The manuscript originally probably had about 440 leaves and 280 illustrations.

This is a page from the Vatican Virgil (Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica, Cod. Vat. lat. 3225). This is one of the oldest surviving illuminated manuscripts, dating to about 400. It is one of only three surviving illustrated manuscripts of classical literature from the classical period. In a one sense, this is where manuscript illumination started. The style is similiar to the frescoes found at Pompeii and in the Roman catacombs. They are typical of late Roman painting, showing an illusionistic treatment of space and modeling of the human form. There are 77 surviving leaves with 50 illustrations. The manuscript originally probably had about 440 leaves and 280 illustrations.

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Todays manuscript

Today's manuscript (British Library, Yates Thompson 26) is a twelfth century copy of Bede's prose Life of Cuthbert. (Bede also wrote a verse Life of Cuthbert). This manuscript was produced in northern England in the last quarter of the twelfth century, probably at Durham. It is know to have been at Durham during the later fourteenth century and early fifteenth century. The manuscript has 150 surviving folios with 46 full page miniatures. This miniature shows Cuthbert setting sail with two disciples. All of the illustrations are set before the gold background within the heavy colored frame seen here. This has the effect of emphasizing the otherworldly nature of the scene. This is after all an illustration of a Saint. This is one of my favorite manuscript pages. I particularly love the way the water is piled up in alternating shades of blue into a mound.

Today's manuscript (British Library, Yates Thompson 26) is a twelfth century copy of Bede's prose Life of Cuthbert. (Bede also wrote a verse Life of Cuthbert). This manuscript was produced in northern England in the last quarter of the twelfth century, probably at Durham. It is know to have been at Durham during the later fourteenth century and early fifteenth century. The manuscript has 150 surviving folios with 46 full page miniatures. This miniature shows Cuthbert setting sail with two disciples. All of the illustrations are set before the gold background within the heavy colored frame seen here. This has the effect of emphasizing the otherworldly nature of the scene. This is after all an illustration of a Saint. This is one of my favorite manuscript pages. I particularly love the way the water is piled up in alternating shades of blue into a mound.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Another manuscript

This is a page from the Escorial Beatus (Escorial, Biblioteca Monasterio, Cod. & II. 5). Beatus of Liébana was an 8th century monk who wrote a commentary on the Book of Revelation. Actually "wrote" is a bit of strong word, as what he actually did was compile a bunch of other writer's comments together. For some reason his Commentary became a very popular book in the 9th and 10th centuries. There are twenty some copies extant, most of which are lavishly illustrated, often with full page miniatures. The Beatus manuscripts are an important part of what is called Mozarabic Art. There existed in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula a tradition of manuscript illustration that was unlike anything else be doing anywhere else in Europe. This tradition emphasized flat, stylized forms for the human bodies. The drapery of the clothes was portrayed as abstract patterns that gave little indication of a body beneath. There was a strong, almost garish sense of color with vivid yellows, greens and reds dominating. The iconography was often startlingly original. It seemed almost as if the entire tradition of book illumination had to be invented anew.

This is a page from the Escorial Beatus (Escorial, Biblioteca Monasterio, Cod. & II. 5). Beatus of Liébana was an 8th century monk who wrote a commentary on the Book of Revelation. Actually "wrote" is a bit of strong word, as what he actually did was compile a bunch of other writer's comments together. For some reason his Commentary became a very popular book in the 9th and 10th centuries. There are twenty some copies extant, most of which are lavishly illustrated, often with full page miniatures. The Beatus manuscripts are an important part of what is called Mozarabic Art. There existed in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula a tradition of manuscript illustration that was unlike anything else be doing anywhere else in Europe. This tradition emphasized flat, stylized forms for the human bodies. The drapery of the clothes was portrayed as abstract patterns that gave little indication of a body beneath. There was a strong, almost garish sense of color with vivid yellows, greens and reds dominating. The iconography was often startlingly original. It seemed almost as if the entire tradition of book illumination had to be invented anew.

This manuscript dates from the 10th century. It has 151 surviving folios with 52 surviving miniatures. It was probably produced at the monastery at San Millán de la Cogolla. It is now in the Escorial.

Monday, January 28, 2008

A manuscript

This is a page from the Quedlinburg Itala fragment. The Quedlinburg Itala fragment was found in the binding of some books from the town of Quedlinburg. It is the oldest surviving Biblical illustrations and is thought to date to the 5th century. The style of the illustrations are similiar to the those found in late Roman manuscripts, notably the Vatican Virgil. The illustrations are heavily damaged. Beneath the illustrations are instructions to the artists on what to paint, giving insight into the working methods of book production during late antiquity.